About

Ember has conducted an in-depth analysis to equip policymakers and campaigners to understand the scale of methane emissions from Australia’s coal mines.

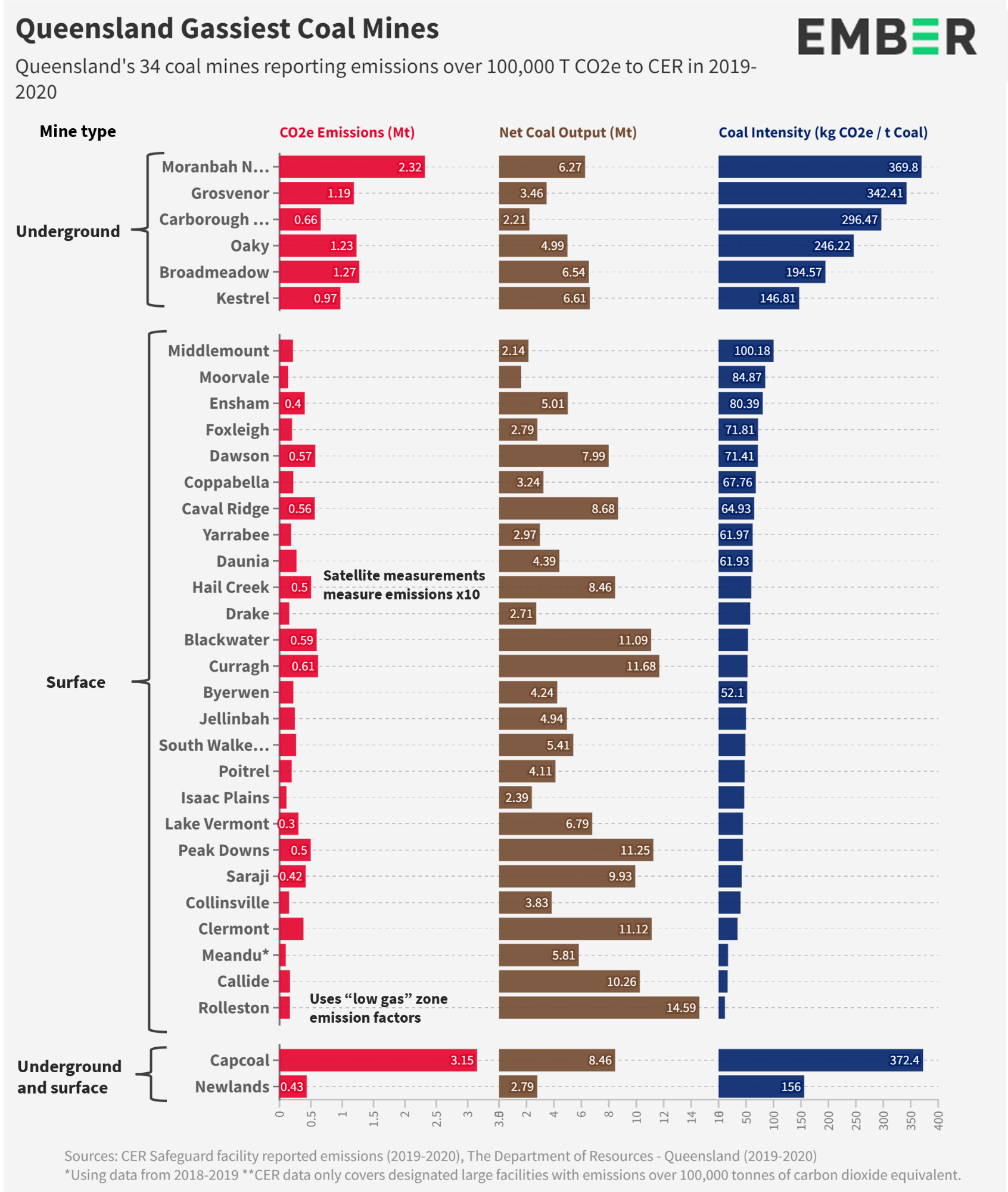

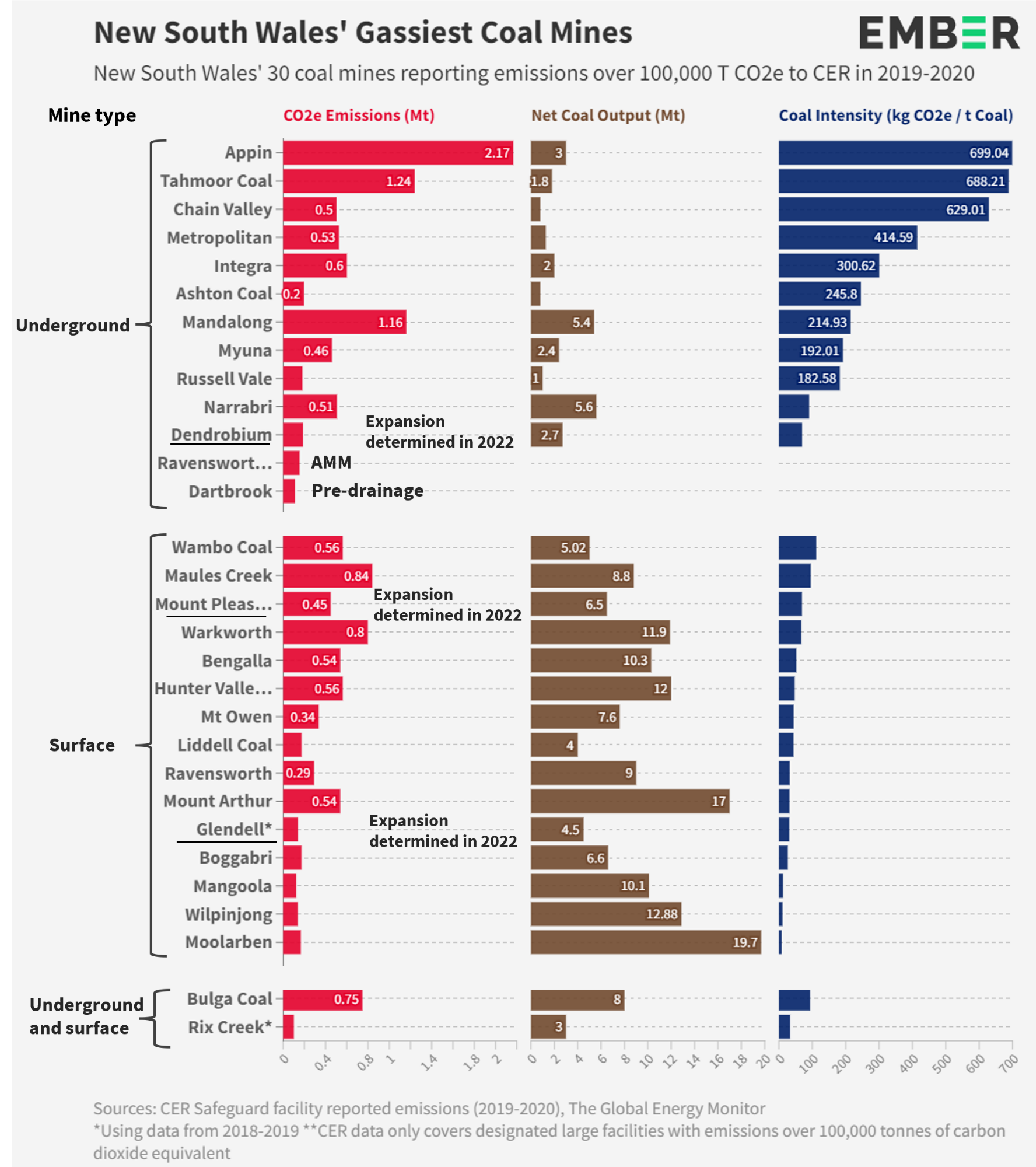

The report provides an overview of the policy levers and practices which could lead to a reduction in coal mine methane, and makes recommendations targeted at improving the measurement, reporting, mitigation and, ultimately, avoidance of coal mine methane emissions. Particular focus is given to Queensland and New South Wales – Australia’s two largest coal mining states.

We assessed data from the Australian Greenhouse Emissions Information System, Clean Energy Regulator, Australian Chief Economist, Department of Natural Resources and Mines, International Energy Agency and Global Energy Monitor.

Executive summary

Methane leaking from coal mines will blow Australia’s already weak 2030 climate targets

Head, International Methane Emissions Observatory

For Australia, one of the world's top five coal producers, an urgent action on methane emissions from coal mines presents an opportunity for the country to become a leader in mitigating emissions in this sector, inspiring change in other coal-producing countries around the world. Ember’s report underscores the challenge Australia is facing to align its decarbonisation pathway with net-zero scenarios. The message is clear - methane from coal mines requires urgent attention. This means not only improvements in measurement and reporting but also, and more importantly, mitigation of these emissions. Coal companies must act now to give Australia a chance to achieve its climate commitments.

Introduction

Understanding the problem of coal mine methane

In this chapter:

The challenge of comparing methane and carbon dioxide

Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a measure to express the effects of GHGs in CO2 equivalent terms. Given that CH4 absorbs much more energy when in the atmosphere, but has a shorter lifetime than CO2, the IPCC considers its impact over 20 years (GWP = 82.5) and over 100 years (GWP = 29.8). One of the shortcomings of this metric is that it assumes a constant value of methane’s effects over time, when in reality it varies significantly.

Historically, the 100-year value has been used by Governments and in major international agreements on the basis that global warming is a long term challenge.

At Ember, we propose to use the 20-year GWP. Climate change is an emergency, and the next 20 years are critical with regards to climate action. Methane’s short atmospheric lifetime means emissions reductions can reduce global heating in the near term.

Throughout the report, we are often required to use the 100-year GWP in order to draw comparisons to Australia’s official reporting on GHGs, and Scope 1 emissions. Whenever possible, we provide both the 20-year and 100-year GWP values.

“Not an either/or” Carbon dioxide and methane do not need to be compared using GWP as only concerted action against both greenhouse gases will address the current climate crisis

The Scale of Australia’s Coal Mine Methane

Australia’s CMM emissions are larger than official estimates

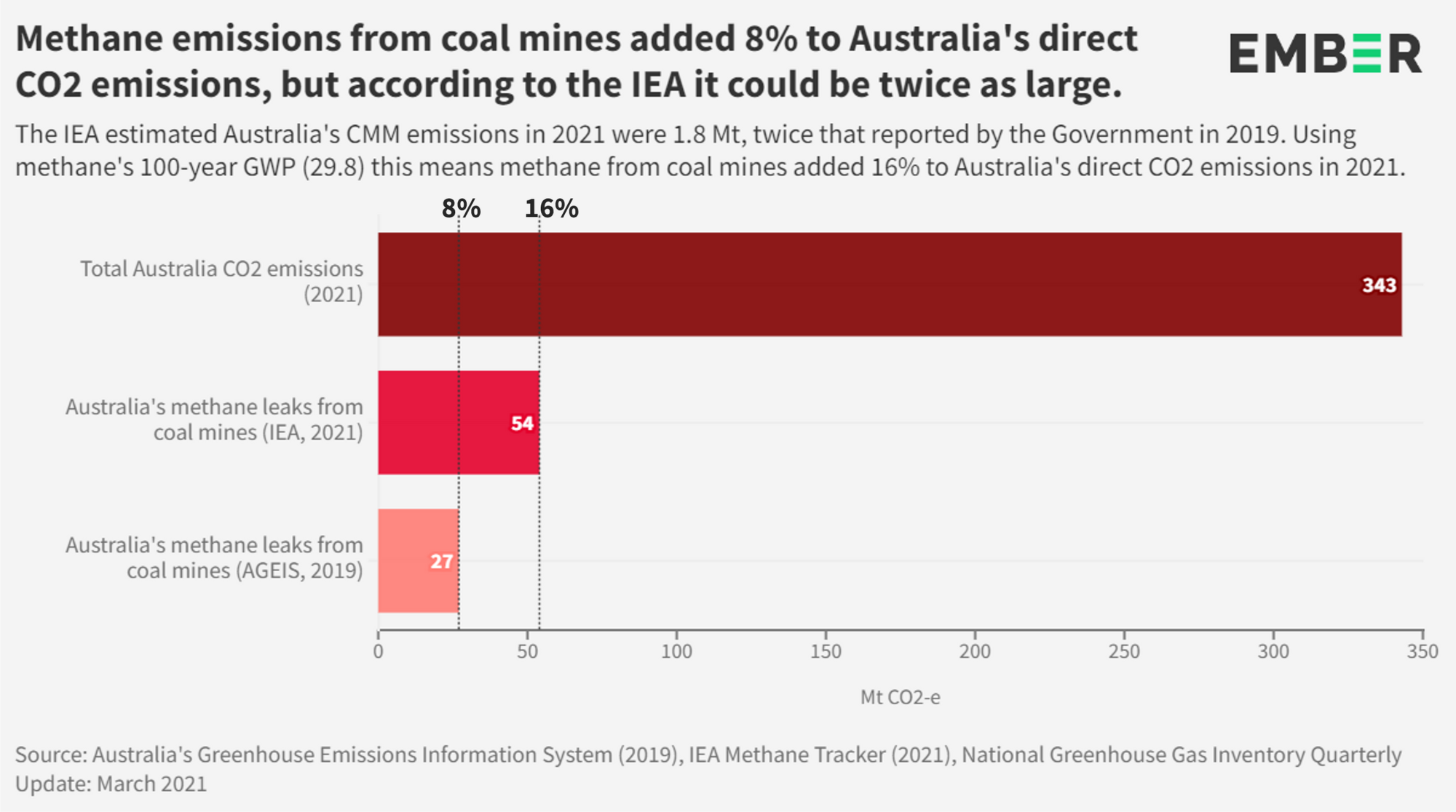

Coal mine methane is the largest contributor to Australia’s energy related methane emissions, but estimates derived from satellite data indicate that the scale of CMM emissions could be far greater. If Australia continues with proposed mines, coal production will be five times the level necessary for a 1.5 degree pathway.

In this chapter:

Methane continues leaking from mines long after mining is stopped. Many mines in Australia remain in “care and maintenance” for years without being fully closed and rehabilitated. The Australia Institute found only eight mines have reached final closure in the past ten years. It is unclear how accurately methane emissions from “care and maintenance” sites are reported.

For example, The Australian Conservation Foundation recently found that in NSW, Ravensworth underground coal mine owned by Glencore had been in “care and maintenance” for seven years and in that time emitted 1 Mt CO2-e equivalent of methane. The mine continues to leak methane emissions to the atmosphere today, with 156 kt CO2-e reported to the CER in 2020.

With such a serious lack of accurate data, the 35 kt of methane recorded by AGEIS at abandoned mines is likely to be a large underestimation. As the number of closed mines is forecasted to increase as more and more mines and associated power stations retire, the challenge of properly closing and reporting on abandoned mines will need to be addressed.

Actions to reduce Australia’s coal mine methane

CMM as the “low hanging fruit” to combat climate change

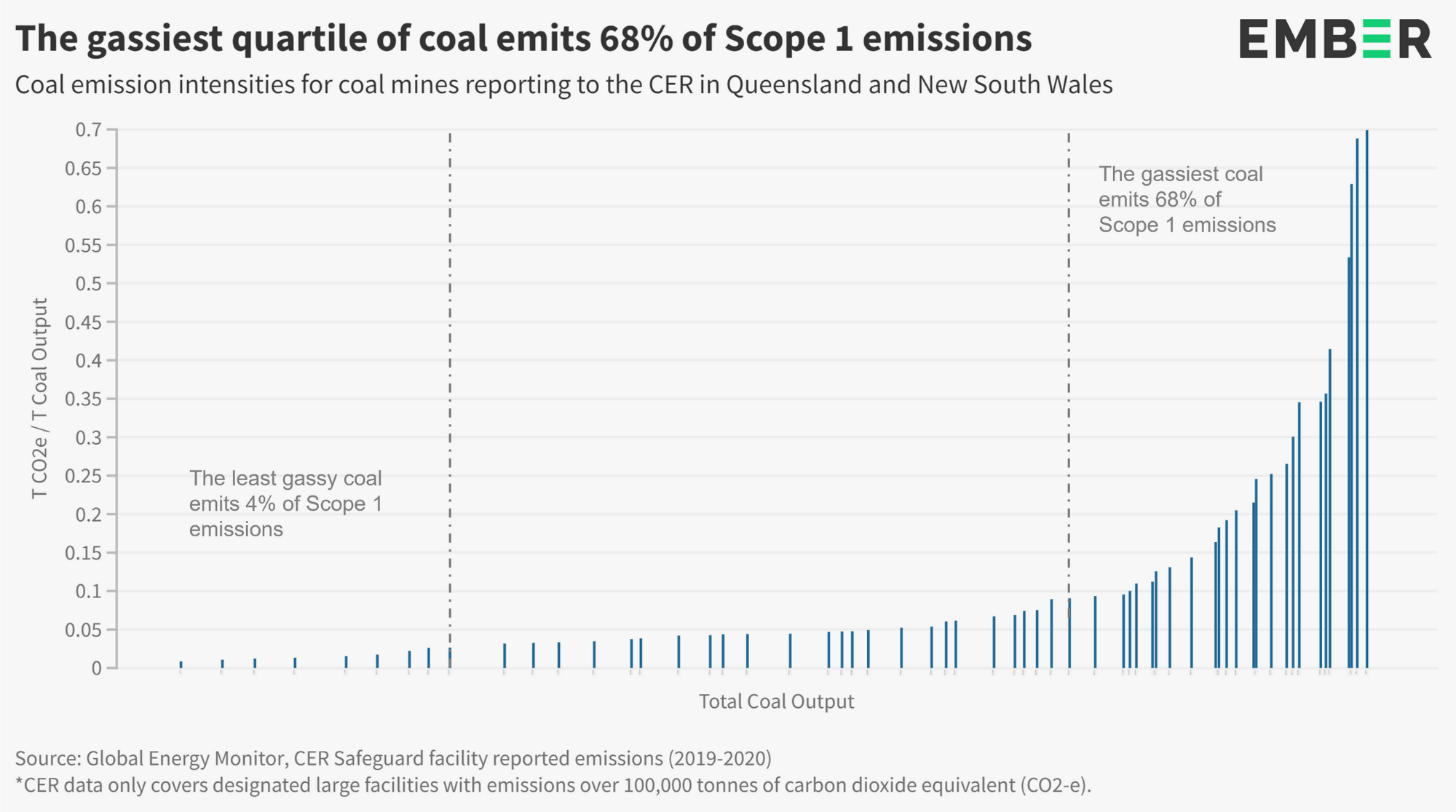

The best way to avoid coal mine methane is to phase out coal, especially by putting a stop to new coal projects and pursuing socially just pathways to early retirement for the country’s gassiest mines. There are also some quick and easy steps like improved monitoring and capturing methane which are the “low hanging fruit” in Australia’s effort to combat climate change.

In this chapter:

Phasing out thermal coal

A report by Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis found that Queensland’s thermal coal is rapidly reaching technical obsolescence and is of marginal viability, with cheaper and cleaner renewables available.

We calculate that 12.5 Mt of CO2-e of methane emissions (100-year GWP) could be avoided if the existing thermal coal mines are closed – equivalent to taking almost three million cars off the road, and reducing Australia’s total GHG emissions by around 3%.

As the IEA has modelled that no new coal projects should be developed and global financial institutions increasingly commit to thermal coal phaseouts, thermal coal mines are increasingly at risk of becoming stranded assets as they struggle to compete with low cost and low carbon alternatives. Additionally, due to the intensity of methane, developing new thermal coal mines is in stark opposition to Australia’s obligation to protect future generations and efforts to reduce GHG emissions.

Supporting Material

Methodology

Sources for emissions calculations

The proportion of methane emissions within total Scope 1 emissions for underground and open cut coal mines were estimated through a compilation of literature, and case studies of Australian mines. Sources included: Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Coal Mining Activities and Their Possible Mitigation Strategies, Environmental Carbon Footprint; Caval Mine Ridge Greenhouse Gases EIA, BMA; Ensham Mine Extension Greenhouse Gas EIA, Idemitsu; Mandalong Mine Annual Review, Centennial.

Emission estimates for the Narrabri Underground Mine Stage 3 Extension Project were calculated using reported estimates of 85% fugitive emissions with 30-40% methane content. Narrabi Underground Mine Stage 3 Extension Project. (2022) NSW Government.

Estimates of methane emissions from thermal mines were calculated as 47% of total CMM emissions in Australia, from IEA estimates on the split of emissions from coking and thermal mines. Source: Methane Tracker 2022.

Estimates of emissions from future mines were based on publicly available information about the lifespan and estimated scope 1 and 2 emissions from the projects, an estimate of the additional emissions was calculated see Appendix A & B.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lock the Gate for participating in the development of this guide, and Courtney Cooper for initiating the work. Thank you to Sunrise and Australian Conservation Foundation for supporting the dissemination of this report.

Reviewed by Conal Campbell, Dave Jones & Sam Moorhead.