Highlights

>60%

The majority of member states reduced peak power demand by 5% or more over winter, as mandated by emergency EU legislation.

€12bn

Reductions in power demand across the EU this winter avoided €12 bn in electricity costs.

40%

With 40% share, renewables generated more EU electricity than fossil fuels in winter for the first time.

About

As Europe headed towards the end of 2022, the ongoing gas crisis combined with low nuclear and hydro output led to concerns about how countries would keep the lights on over winter. Now, looking back over the last six months, it is clear that Europe’s power system successfully rode out the storm. This analysis examines power generation and changes to electricity demand across EU countries in the winter months to understand what happened over the winter, and what lessons the EU can take forward.

Executive summary

EU power system weathered the winter

A significant decrease in electricity demand combined with record renewable electricity supply prevented the EU from returning to fossil fuels this winter.

Senior Energy & Climate Data Analyst, Ember

Europe faced a crisis winter, with spiralling energy costs and supply concerns triggered by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The EU got through those difficult months, but it can’t rely on emergency demand cuts and mild weather for future years. To keep power supply stable, the EU needs to divorce from fossil fuels as quickly as possible.

Power generation over winter

Powering through winter

Renewables produced more EU electricity than fossil fuels this winter, as a drop in demand and record wind and solar generation led to decreased coal and gas power.

In this chapter:

Bulk demand restrictions

Widespread demand reduction

Nearly all EU Member States cut electricity consumption this winter compared to their five-year average, but only a handful achieved the voluntary target of a 10% reduction. Total EU electricity consumption was 6.2% lower than the five-year average.

In this chapter:

These reductions in electricity demand will have multiple contributing causes. Among the primary causes are likely to be government mandated reductions, voluntary acts of solidarity and economically motivated changes to reduce bills (demand elasticity).

From the perspective of energy system security, demand reductions are a positive outcome. However, not all reductions in consumption will be sustainable or desirable either economically or socially. Decisions taken by individuals or businesses to consume less electricity may have come at the cost of comfort or production. Where reductions have been achieved sustainably, for example as a result of reduced wastage or smarter consumption, the gains should be consolidated.

Examining consumption patterns by sector can help to explain the origins of demand reduction, but such data is not yet available for the winter period, nor 2022 in general. However, proxies such as industrial production can provide insights. Industry consumed 44% of electricity in Germany in 2021, almost as much as buildings. German industrial production in 2022 was only 0.6% lower than 2021, and 5% down from 2019. The latest statistics for 2023 show that consecutive growth in January and February “more than compensated the significant decline in December 2022”. It therefore appears unlikely that lower industrial output alone can account for electricity demand reductions of 5-15% observed across the winter months in Germany.

Peak demand reductions

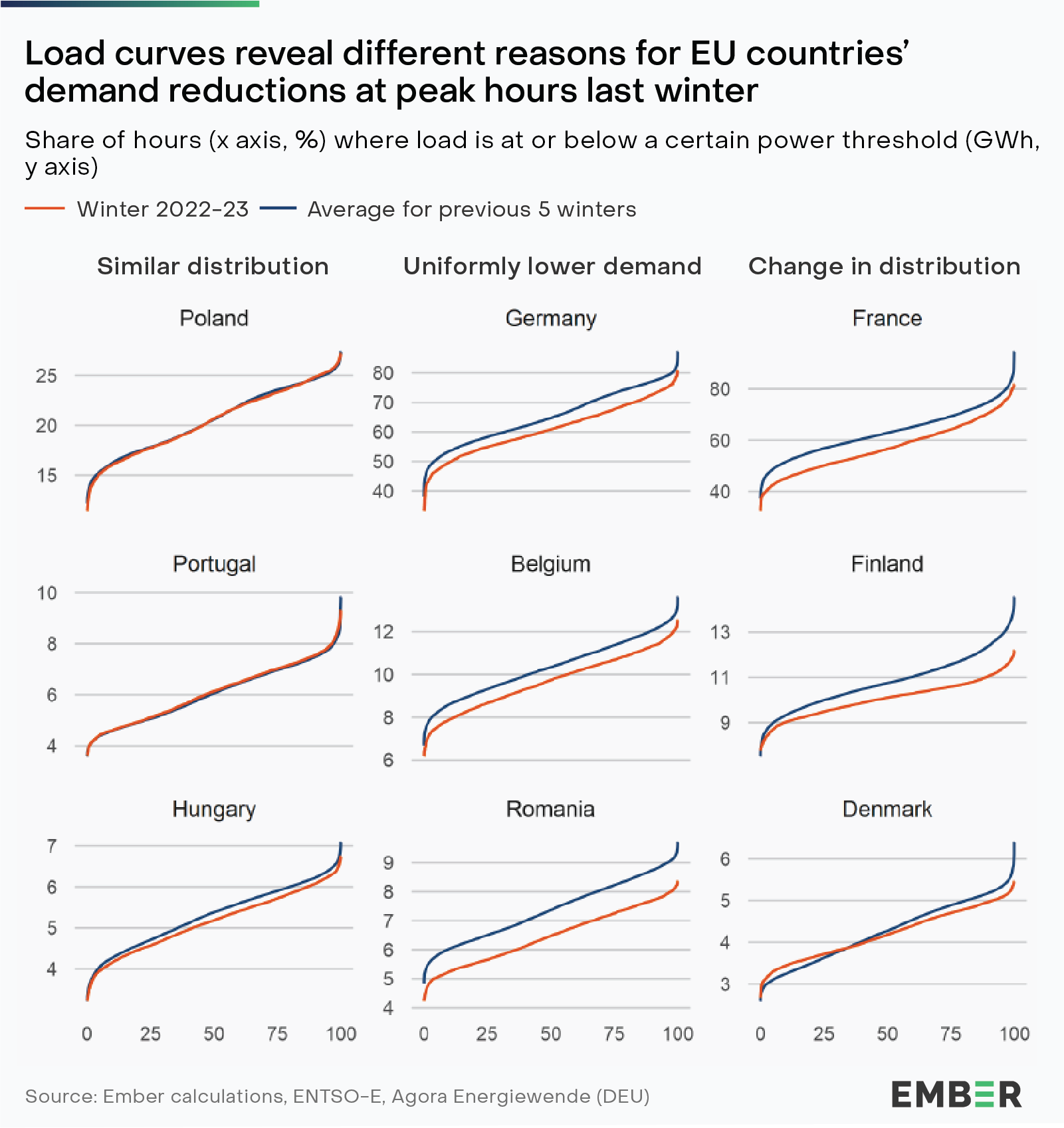

Majority of EU countries on target for peak demand reductions

The majority of member states reduced electricity demand during ‘peak hours’ by the mandatory 5% or more. All but one country for which adequate data is available (Ireland) reduced peak demand to some extent. These peak reductions almost certainly lowered system adequacy risks this winter and limited the occurrence of even more extreme price spikes.

In this chapter:

Power system flexibility will need to rapidly increase to enable the integration of sufficient renewable electricity to decarbonise the power system.

The European Commission anticipates power system flexibility will need to more than double by 2030 to enable renewable targets to be reached (133% increase in GW terms on daily timescales). Flexibility from demand, such as that observed this winter, will be an essential, low-carbon source of flexibility that has the potential to reward consumers for using electricity at times of surplus and reduce power system load when supply is tight.

There is huge potential for demand flexibility, the majority of which is from households, but commercial and industrial activities can also meaningfully contribute. While data is scarce, it is claimed that at least 13 GW is active in EU markets today (i.e., the amount represented by the smartEn group). This is compared to an estimated potential of 164 GW of upward and 130 GW of downward flexibility by 2030.

This winter has shown that it is possible to reduce consumption during peak hours using demand flexibility options that are available within the existing market framework, including voluntary actions. Nevertheless, fossil gas remains the largest provider of flexibility to the European grid. To change this, the package of electricity market reforms proposed by the European Commission rightly aims to provide additional tools to support non-fossil flexibility. Notably, the package includes an obligation for member states to assess their flexibility (and storage) needs and report on these from 2025, including in National Energy and Climate Plans (NECPs). Member States are also encouraged to introduce new support schemes in order to promote demand-side flexibility, possibly including a form of capacity payment. The package also emphasises the importance of fully implementing the existing Clean Energy Package from 2019.

In addition to the proposed actions and reforms, it is critical that the experiences of this winter are evaluated and learned from, in order to consolidate the progress made towards a more flexible and, therefore, secure European power system. A system that fully utilises demand flexibility will be cleaner due to better integration of renewables, and cheaper due to less extreme price spikes and reduced reliance on expensive fossil fuels.

Conclusion

Falling demand wipes out fossil generation and heralds a more flexible future

This winter showed that Europe’s increasingly renewables-based power system can remain resilient even in a difficult energy context.

Emergency measures to reduce power demand had a demonstrable impact on security of supply in Europe this winter. With record renewable supply too, fossil fuels continued on their downward trajectory, countering claims that Europe turned back to coal in response to the gas crisis.

Power demand fell in nearly all Member States compared to the five-year average. Any demand reductions that can be maintained sustainably should be. This will accelerate the transition away from fossil fuels by reducing demands on Europe’s grid infrastructure and limiting the need for future investment, which will nevertheless remain sizable.

Any improvements to demand flexibility over the winter should be evaluated, consolidated and quickly built on. The recently proposed electricity market reform presents an invitation to seriously consider demand flexibility, and introduces new tools to enhance this vital service. The energy system of tomorrow will require more flexibility to fully reap the benefits of cheap wind and solar power. Demand flexibility is one of the most cost-effective ways to deliver it.

Ultimately, the EU navigated this winter due to a combination of emergency measures, mild weather and citizen action, however, these should not be relied upon in future to protect against the risks to security of supply created by fossil fuel reliance.

Looking beyond this winter, the EU is already putting plans in place to transition away from fossil fuels permanently, with an increased renewable energy target and many more ambitious national targets already in place. Markets are also responding, with key clean technologies growing at a dizzying pace. The destination is clear: the EU is on its way to a clean power system, and that shift has gathered pace in the past year. Putting policies in place to accelerate the delivery of a clean, renewables-based power system is the best way to ensure that the EU is never faced with a winter like this again.

Supporting Material

Downloads

Methodology

Winter definition

‘Winter’ in this piece refers to October of the stated year to March of the following year. ‘Winter 2022’ means in this case October 2022 to March 2023. Analysis of bulk and peak reduction uses the period November 2022 to March 2023 as this is the period to which the emergency EU legislation (and targets) applies.

Calculating the value of saved electricity

Electricity ‘savings’ (TWh) are defined as the difference between monthly demand this winter and the average demand for the same month over the last 5 years in each country. To calculate the value of this saved electricity, the TWh value per country is multiplied by the average day-ahead price over the month in that country.

Identification of peak hours

We identify peak hours in a way that matches as closely as possible to the definition set out in the emergency EU legislation. The legislation states that “Each Member State shall identify peak hours corresponding in total to a minimum of 10% of all hours of the period between 1 December 2022 and 31 March 2023′. ‘States shall reduce gross electricity consumption by 5% on average per hour’, where ‘peak hours’ means individual hours of the day where, based on the forecasts of transmission system operators and, where applicable, nominated electricity market operators, day-ahead wholesale electricity prices are expected to be the highest, the gross electricity consumption is expected to be the highest or the gross consumption of electricity generated from sources other than renewable sources is expected to be the highest” (p37).

As the forecasts of transmission system operators are not readily accessible, we used historical hourly data to identify the 10% of hours qualifying as peak. We were able to collect reliable hourly data for 24 member states dating back to November 2017 (hence providing a full 5 years of reference data prior to this winter). For each country, we calculated the average demand in each hour of the winter period. The ‘peak hours’ were identified as those hours in the top 10% for average demand over the reference period. Unlike the legislation, we included November in the reference period, to maintain a consistent definition of the winter period for demand analysis. The impact of including November in the peak demand analysis is not significant, as only 8% of the peak hours we identified fell in November.

Across all countries most peak hours are concentrated in January (44%) and the lowest fraction are in March (3%).

Correction note

A previous version incorrectly stated that Germany and Poland were responsible for 70% of the reduction in EU coal generation this winter, with decreases of 9 TWh and 4 TWh respectively, this was updated 27/4/23

Acknowledgements

With thanks to Agora Energiewende for providing high quality open data on the German power system. With thanks to the European Environmental Bureau for their research and tracking of energy saving measures in force across Europe.