About

This briefing compares scenarios on the future of the UK power sector which have been developed by three independent groups, and examines the key technologies and policies that will lead the electricity system towards cost-effective decarbonisation.

There is now broad consensus among experts behind the Climate Change Committee’s recommendation of a phase out of unabated gas in UK electricity generation by 2035.

Executive summary

UK can lead the world in a gas phase-out

The Sixth Carbon Budget The Climate Change Committee

Building on the phase-out of coal-fired power generation by 2024, no new unabated gas plants should be built after 2030, and the burning of unabated natural gas for electricity generation should be phased out entirely by 2035. That is achievable with the cost-effective deployment of renewables, gas CCS, and hydrogen at scale.

Introduction

100% clean electricity brings multiple benefits

The Government’s recent enshrining in law of a 78% reduction in UK greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2035 (compared to 1990 levels) will lead to a major shift in the UK’s energy system in the coming decade. The Government now needs to strengthen its strategy for meeting that target. Key to that will be the phase-out of unabated gas-fired electricity generation in the UK, effectively removing the last major source of power sector emissions. Several pathways have been put forward to address the question of how and when the phase-out of unabated gas power should take place and this briefing examines the main features of three prominent pathways: the Sixth Carbon Budget by the Climate Change Committee (CCC), Energy Systems Catapault’s (ESC) modeling for Good Energy, and National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios 2021.

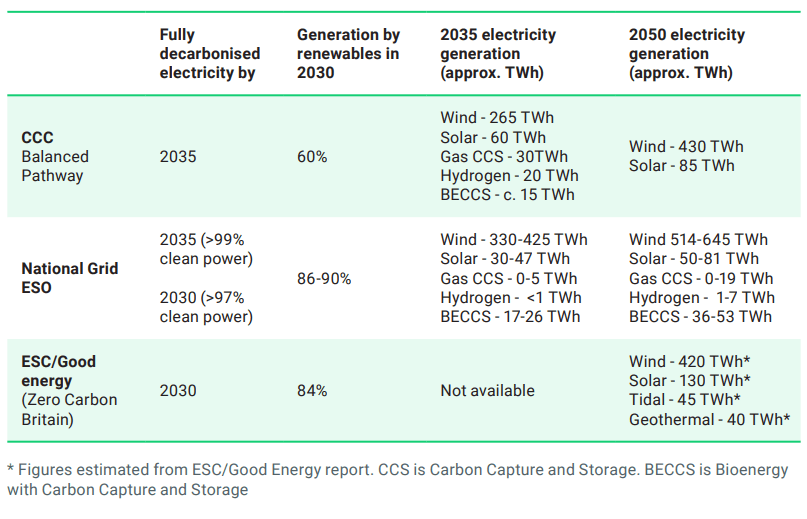

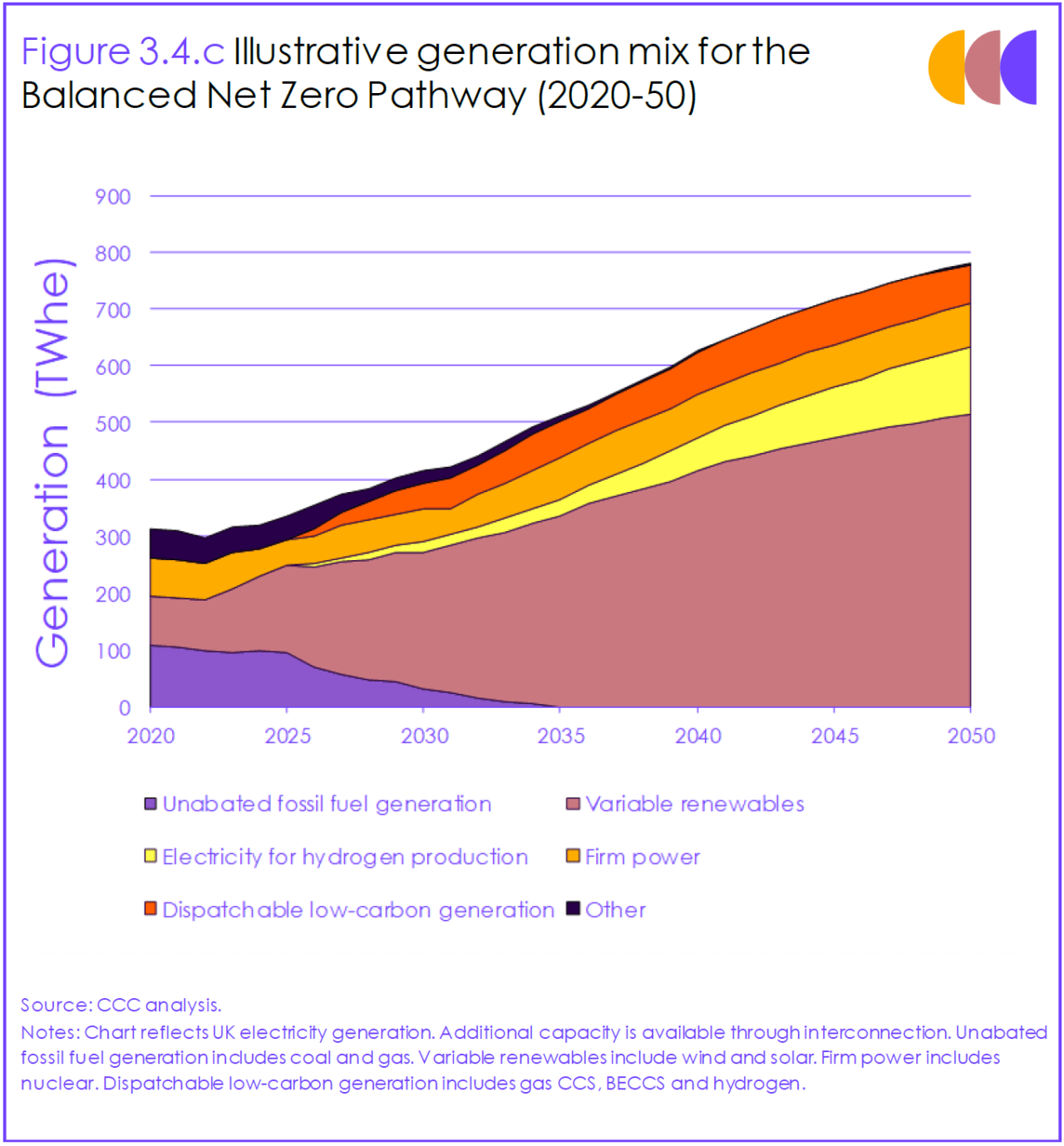

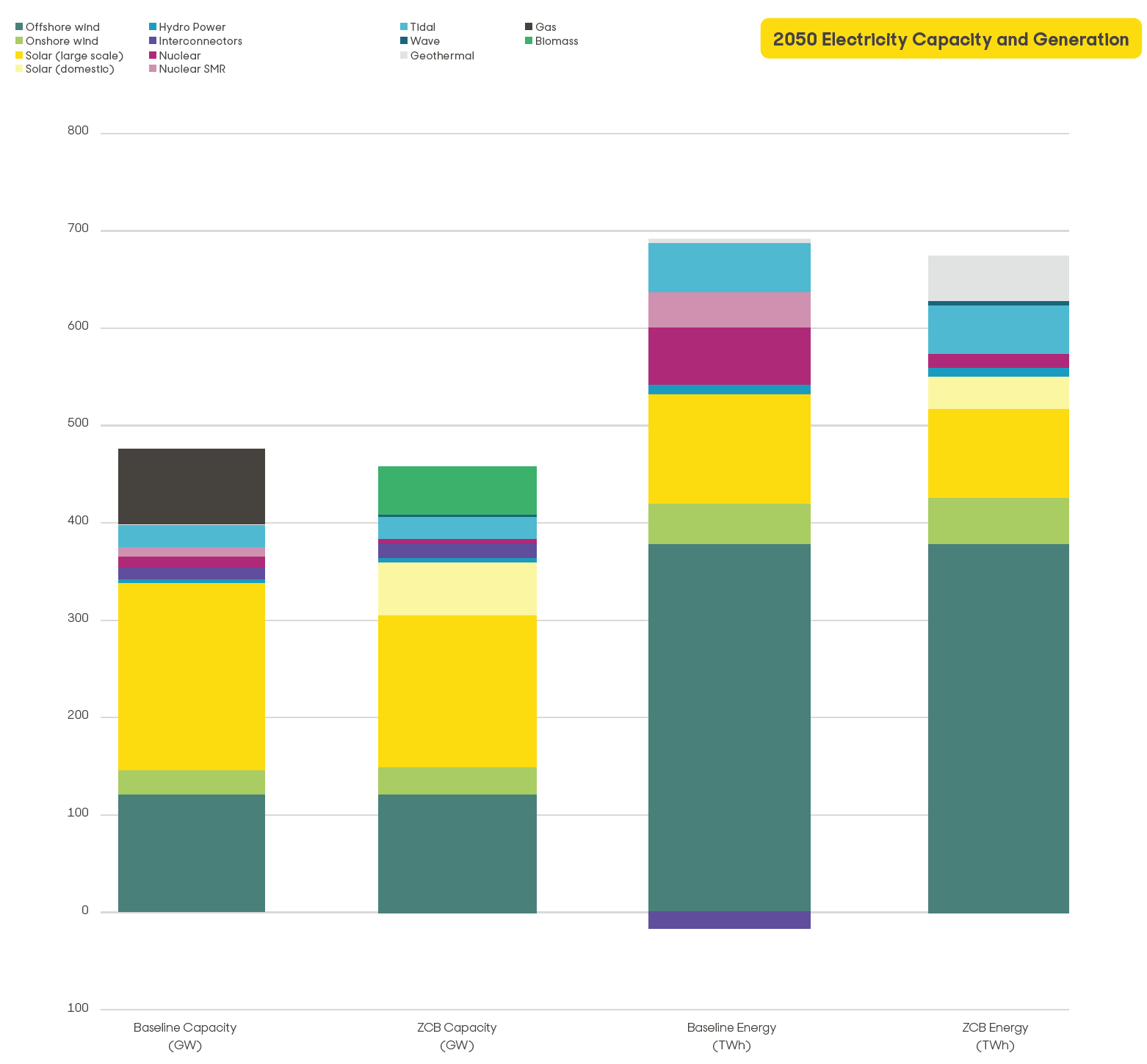

In the Sixth Carbon Budget, the CCC advised the Government to phase out unabated gas power by 2035 in order to meet the 78% GHG reduction target – a similar timeline to the IEA’s Net Zero by 2050 roadmap, which proposes net zero power sectors in all OECD countries by 2035. The ESC modeling indicates that a fully decarbonised electricity grid can, however, be achieved sooner—by 2030—through a more rapid expansion of renewables if more supportive policies are put in place. In this year’s edition of their annual Future Energy Scenarios, National Grid set out three credible pathways to reach net-zero by 2050 and found that each scenario requires significantly less than 1% unabated fossil fuels by 2035, with more than 80% of power generation supplied from wind and solar.

Irrespective of the pathway chosen, there is a broad consensus that signalling an end to unabated gas power delivers benefits beyond simply meeting emissions targets. It provides opportunities to promote energy self-sufficiency, low-cost electricity, and champion British businesses involved in delivering clean energy. The Government has already committed to reducing the UK’s contribution to climate change by ending support for fossil fuel energy overseas in March this year. The CCC’s advice to phase-out unabated gas power by 2035 presents an opportunity to now adopt a similar approach for the UK.

Why act now?

Concrete action to cut emissions taken in the short-term will build confidence in the Government’s net-zero vision for the UK. A rapid transition to a clean power sector unlocks decarbonisation everywhere else in the economy, through electrification of heat, transport, industry and more. The success of the UK coal phase-out, announced in 2015, demonstrates that climate leadership and levelling up the country go hand in hand. And rather than raising electricity prices and increasing our dependence on expensive gas sourced from overseas, as some feared the coal phase-out would lead to, it instead ushered in a new generation of low-cost renewable energy technologies, diversified electricity supply, created new skilled jobs across the country, and brought much needed investment to the UK’s electricity infrastructure, yielding benefits to both business and consumers years ahead of the official phase-out deadline. The gas phase-out can repeat that success.

Lower electricity bills

This year’s rocketing energy bills are being driven by the growing cost of imported fossil gas. The monthly average day ahead price had more than doubled over the course of December 2020 to January 2021, a trend that a forthcoming briefing from Ember will dig deeper into. The UK can move quickly to reduce fossil gas imports by generating an increasing proportion of its electricity from much cheaper wind and solar power.

International impact

Later this year, the UK will host the United Nations Climate Change Conference (COP26) and our ambition and record on tackling climate change will come under international scrutiny. The UK has been gifted with an opportunity to capitalise on the hard won successes of its decarbonisation strategy by committing to the phase-out of unabated gas-fired electricity generation by 2035. Both the CCC’s Sixth Carbon Budget and National Grid’s Future Energy Scenarios reports show this is well within our grasp, while analysis by Ember shows wind power has already pushed gas use in the UK to a 5 year low.

Announcing a phase-out of unabated gas power would also extend the UK’s ambitions ahead of those of continental Europe and help to cement transatlantic ties with the Biden administration, which in April 2021 published its own plans for fully decarbonising the US electricity sector by 2035.

A green industrial revolution

As the UK re-asserts its economic and political independence, the country can take advantage of access to an abundance of coastal areas suitable for offshore wind development to achieve energy security, cut electricity costs, and reduce dependence on imported fuel and electricity in the process. Indeed, the Offshore Renewable Energy (ORE) catapult suggests the almost limitless potential of UK offshore wind can lead to a boom in green hydrogen which “can match best years of North Sea oil and gas”. Drawing a line under fossil gas brings the UK one step closer to a future where we are an energy and technology exporter, not importer.

Finally, the Government has committed to levelling up the UK economy by supporting communities across the country. Renewable energy is one of the fastest growing sources of employment in the UK, providing skilled jobs and distributed benefits, particularly for areas bordering the North Sea. Indeed, the UK’s green economy is now four times larger than its manufacturing sector. A phase-out of gas in power will make it easier for renewable electricity providers to secure investment in new capacity, creating more opportunities in these regions, including for those recently employed in the oil and gas industry.

Models

Comparing models by the Climate Change Committee, National Grid and Energy Systems Catapult

In this chapter:

Conclusion

Many benefits and few risks to phasing out gas power

Multiple independent models agree that phasing out unabated gas-fired electricity generation by 2035 is essential to meet the UK’s legislated carbon targets, and carries few risks if government decisions are made swiftly for a smooth transition.

All the models agree that renewables will be at the core of this transition, especially offshore wind and solar, and so the Government’s focus must be on ensuring rapid deployment in those sectors. A step change in capacity for energy storage is also essential in all scenarios, as is a growing hydrogen sector. In all models we assess here, unabated gas power has been reduced to just a few percent of total annual generation by the end of this decade.

The models disagree on the size of the role for gas CCS and nuclear, but suggest that they will likely play a role in stabilising the 2035 grid, albeit a small one.

If a strong commitment is made by Government in 2021, the UK grid can be almost free of the cost and emissions inherent in fossil gas use by the end of this decade, and have fully eliminated it from the power sector by 2035. Such a phase-out could help accelerate the green industrial revolution in the UK, as well as forge new international partnerships united in the transition to clean electricity. COP26 serves as a platform to demonstrate leadership and multilateral cooperation on climate change. Committing to a gas phase-out now will enable us to deliver net-zero by 2050.