Breadcrumbs

As aluminium surges in China, so do carbon emissions

China’s aluminium production grew by 5% in 2020, producing more emissions than Indonesia

Available in: 简体中文

About

This paper assesses the latest full-year data from China official production and trade data and from the International Aluminum Institute. It reveals the scale of carbon emissions behind China’s coal-backed aluminium manufacturing, alongside recommendations for next steps.

Executive summary

Key findings

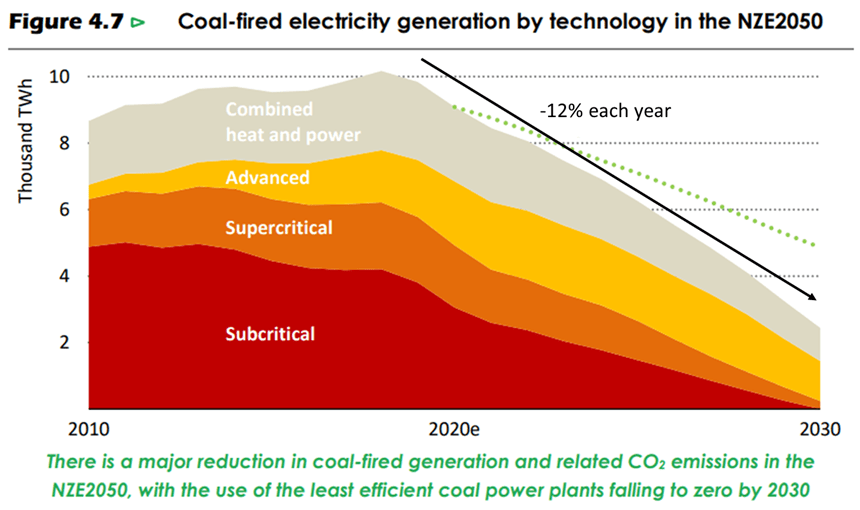

The aluminium sector in China needs an urgent wake-up call to phase out its captive coal capacity in just the next 10 years.

Senior Electricity Policy Analyst, Ember

Emissions from China’s aluminium sector are immense, and the sector needs to face the same urgency to reduce its coal reliance as the electricity, steel and cement sectors. China’s transition towards a low-carbon energy future needs aluminium, especially in solar panels, electric cars, and electricity cables, but aluminium can’t play that role when it’s so reliant on coal. Redressing this challenge requires immediate actions to phase out the large fleet of subcritical coal capacity dedicated for aluminium production in China.

China's growing appetite for aluminium

The sector sees healthy growth, despite pandemic pressures

Aluminium's coal problem in China

Coal-fired electricity makes aluminium an emissions-intensive sector

In this chapter:

Prof. Huaping Sun School of Finance and Economics, Jiangsu University

In view of its commitment to carbon peak before 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060, it is critical for China to redress the carbon footprint of its energy-intensive industries. China’s primary aluminium production is overwhelmingly reliant on inefficient subcritical captive coal power plants, resulting in large CO2 emissions. To rectify the situation, China needs to accelerate the deployment of renewable energy and low-carbon production technologies in the aluminium industry.

Conclusion

Possible options for action

Clearly, urgent actions are needed to push China’s aluminium sector to phase out its subcritical captive coal power plants in 2020s. Some possible options for facilitating this coal phase-out, that may be worth considering, are presented below.

Efficiency improvement at the production side can help reduce the electricity intensity of aluminium production, hence making some of the existing subcritical captive coal capacity redundant. Although China’s aluminium sector is relatively more efficient, when compared with other countries and regions, there is always some scope for further improvement.

Supporting Material

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express his appreciation to A Prof. Wenbo Li, A Prof. Peng Wang, and Prof. Huaping Sun for their thoughtful comments, which helped to improve the quality of this paper. The author is, of course, responsible for the contents.